Introducing Agency

A topic that has come up a lot in my Premodern podcast, Spike Colony, is "agency" in Magic: The Gathering.

Agency can apply to many individual elements, aspects of duels or games, or slivers of broader entities; like decks or strategies. A lot of smart people have been talking about agency like it's card advantage; when in fact, it's more like tempo right now. Perhaps, as with pornography, we believe we know agency (or can identify its absence) on sight. Perhaps! But I'd guess we're not all always talking about the same things that we see. This article is an attempt to formalize the concept and establish a common language.

Agency is a thing. More specifically, it's a quality. Most Magic players in most contexts have some. Some have more and some have less. Some see more in the opponent and some fail to even when it's all over them. Don't worry, for a moment, if you want more agency. Agency is a thing, but having more of a thing is not necessarily good. Do you want more strongman authoritarianism? More erectile dysfunction? Remember: Almost everyone has some of this thing; but more of it might or might not mean that you'll actually win more.

To me, agency is increased by two phenomena:

- The presence of decisions you can make

- The impact those decisions have on the outcome of a game

Generally speaking, the more of either input, the greater agency you have. The less of either, the less agency.

This is purely normative and speculative, but I believe that having high agency (even if you make mistakes) scales with the potential pleasure a player has in a game of Magic. Think about the long, hour-eating, untimed Top 8 games where two Control players sit around doing nothing until they flurry into doing everything (and then fall back into chip shots or inaction after both have exhausted their resources). These are the games where one will say, "Whether I win or lose, this was a great game," or where onlookers cheer at an opponent-exhausting Siphon Insight or the 10th poison counter from the final, unchecked, Mirrex token. Both players did lots of stuff. The early game may or may not have been rocky for one of them. Both played. Both got to show off what their decks are supposed to do in one way or another. Lots of decisions were made as a result of lots of turns having been played; at least some of those decisions mattered. Mistakes, inevitably, happened on both sides; but whether or not anyone identified anything short of a catastrophic blunder is always up for debate. Everyone can agree it was a great game.

Having less agency (even if you win) tends to be lumped up with games that are less fun. I've cashed in more than my fair share of first-turn Phyrexian Dreadnoughts with Daze / Foil backup... But never once kidded myself that that was the game play that made me love Premodern.

Let's explore some very easy to digest illustrations of agency:

- You're manascrewed. You might have had a decision you could make early in the game (to mulligan or not to mulligan, that is the question...) but after that you could not even decide what land to play, as you had none. Forget about casting any spells! You had fewer decisions due to lack of resources; as such, the second half of the agency equation never even came into it.

- You're mana flooded. You might be able to make some decisions (which of the many lands in hand should you play?) but your other decisions don't have much meaningful impact on the outcome of the game; that, or there weren't very many of them.

- You're playing the Lost in the Woods deck.

Aside: The Lost in the Woods deck

- 1 Lost in the Woods

- 40 Forest

Though I've heard of versions that were as much as...

- 1 Lost in the Woods

- 44 Forest

The thesis of the Lost in the Woods deck is that you drafted Lost in the Woods. You could then gamble on a potential 41-card deck that lived and died by Lost in the Woods.

You could have Lost in the Woods in your opening hand. If you did, you'd be able to play it on turn five. You'd have to be able to, because all your other cards were basic Forests. Now, with Lost in the Woods on the battlefield, opposing creatures would not be able to beat you, at least not unassisted.

The Lost in the Woods deck was a triumph of Limited creativity... But also risk-taking. You could lose to a single Disenchant effect. What if the opponent had hand destruction or a Counterspell? Though a gamble, the average deck couldn't beat one Lost in the Woods. End. Stop. Fin.

Now if you drew Lost in the Woods in your opening hand, you'd just cast it on turn five. If you didn't? You could mulligan six or even seven times looking for it. Note: Going down to no cards whatsoever still didn't stop this one-card combo! If Lost in the Woods were in the top five cards of your deck, you'd have it in play as quickly as if you had it in your opener, at least going second. Depending on your opponent's clock, you still might have it before it was too late. Also note: The decision to mulligan potentially to zero isn't really an act of agency; it just exhibits you know how the deck is supposed to work.

The Lost in the Woods deck is a good example of a deck where no one has much agency.

You have to be balls-y to play this deck. You are defeated by an opponent with a Jon Becker special. You're often defeated by some kind of Duress; some kind of Disenchant... But if the opponent doesn't have those, they're cooked if Lost in the Woods hits. If they're planning on winning with creatures, they have low agency. They can make the best, most varied, decisions in the many planes of Dominia... And be unable to positively affect the outcome of the game.

For you? You have a formula you play by, but outside of that, your choices are which Forest art you play, assuming you don't have 40-44 matching Forests. Outside of that? You cede all agency to your opponent! If they have the right kind of card before they run out of cards, they win. If they don't, you win.

The Lost in the Woods deck can be supremely satisfying for you to play, because the single decision you make - to gamble that your opponent can't beat Lost in the Woods - is so high impact. That is a very narrow, but very Very VERY tall, area under the agency curve. But from the other side?

Some people really didn't understand how this worked, or how brilliant you might be for gambling on it:

As this reddit poster notes, one of the fault points is your switching into a "normal" deck. There was a lot of gamesmanship available. What if you won the first game and you knew your opponent didn't have hand destruction, permission, or Disenchants? Might be a good sideboard swap. Or you could start with it for the free win, and swap into your mediocre regular deck... But your opponent is now a five-color monstrosity splashing one basic for enchantment removal and one for an off-plan Mill effect. This is obviously the kind of thing I love, because clever.

As you can see the amount of agency doesn't have very much to do with the amount of winning a single game here.

End aside.

Decks that are often described as low skill are often just low agency. White Weenie in contemporary Magic is a good example. You play your Recruiter or Skrelv on turn one; you lucksack into Thalia on turn two; oh look, you've hit the Adeline lottery on turn three. A monkey could do it! You're playing all at sorcery speed. Your decision is basically whether or not you want to play your monstrous, undercosted, threat on curve or not. What do your cards do? They mostly attack.

Your decisions are - generalizing a little here - largely made for you. Play a land; play the on-curve creature. Does it add power? Make your potential attackers harder to stop? Send.

Editorializing again: My feeling is that it's annoying to lose to low agency decks.

Some decks are high agency but mistaken as low agency by people who don't understand their game plans. Red Decks of at least some eras can be lumped into these piles.

To be fair, the 1998 Regionals-era Sligh deck with Mogg Flunkies (can't even block, can barely attack) was a lucksack's dream. That deck was probably overpowered relative to the field, and suffered from being limited in its Gears. But today's Red Decks across many formats are far more nuanced. Sure, if you only know about Gear One you're going to play kind of like a White Weenie player; but even then you have twice the decisions because you have a mix of creatures and spells; and because your spells can often target players, a creature, or some other creature. The dumbest Red Deck player has three times the agency of the average White Weenie player if only because spells as a class are more high agency than creatures as a class.

The Skill of Magic: 1993 to 2023

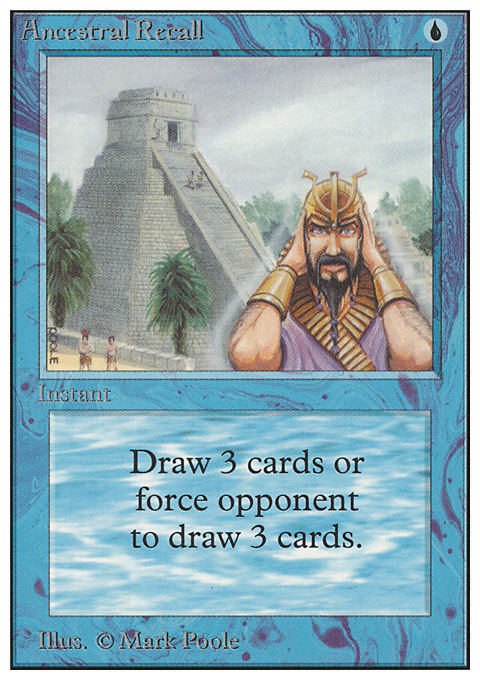

In 1993 this was the first showcase cycle of Magic's inaugural release:

Poor White, am I right?

Ancestral Recall has been Restricted in Eternal formats for longer than I've played competitive Magic and even Dark Ritual has had its day in the dog house. Lightning Bolt was generally thought of as too good for Standard-level play, on its pure efficiency. It remains a Modern Staple.

But if you think about Lightning Bolt from a mana-to-damage perspective, it's actually less efficient than almost any creature that gets to attack more than once.

Consider for a moment the showcase cycle from Magic's first set in 1993, to the last set released 30 years later:

Many longer tenured players would identify something they'd call power creep, which I don't know is 100% accurate. I don't think you can argue that the The Lost Caverns of Ixalan cycle is "better" or "more powerful" than the Alpha boons. They're not more powerful than Ancestral Recall, and it's dubious any of these cards is going to see broader play than Lightning Bolt. But what they showcase really, really, clearly is the philosophical skill delta between the design eras.

Even if Ancestral Recall was powerful, it was one shot. Lightning Bolt is the best example because it was one-shot and you had to pick something (player, creature, some other creature... In contemporary times maybe a Planeswalker). You had to make a decision, and subsequently, exercise agency on two axes.

Aclazotz, the most successful tournament card of the "Deepest" cycle so far, is the opposite. It's not only not one-shot, your opponent can barely get rid of it. You can screw up a lot, either by making decisions or not, but the impact of those decisions on the outcome of the game is lessened by the overlapping advantages inherent in Aclazotz's design.

If you make great decisions with Aclazotz... Do they impact the game very much relative to medium decisions? The card has lifelink and is a perpetual source of cardboard advantage.

If you make terrible decisions with Aclazotz... Are you particularly punished? It's just going to come back, bail you out, and lifelink you out of the hole you dug yourself, even if you throw it away carelessly.

I'm trying very hard to divorce this analysis from judgment, but I think it is a fair observation to say that Lightning Bolt from a design philosophy perspective is very far from Aclazotz, Deepest Betrayal // Temple of the Dead when considering agency.

Agency and Inevitability

Let's go back to The Lost in the Woods deck for a second. Imagine in fact it's the 44-Forest version that really, really, doesn't want to get decked.

If this were a regular deck, Limited or Constructed, we'd look at a deck with 44/45 mana and assume that it had a high likelihood of losing to mana flood. But understanding the deck, we know that it is designed to be able to cast Lost in the Woods exactly on turn five no matter what its draw, even if it mulligans aggressively. Surely this deck can lose, but never to mana flood. The large number of lands is a driver of its inevitability, not the usual diagnosis.

Compare that to most decks - especially most Constructed decks. Most Constructed decks, across eras, play about twenty-four lands. Tsuyoshi Fujita's Red Deck Wins from Extended 2004 - tons of initiative-taking one-drops - was still a twenty-four land deck:

Red Deck Wins | Extended | Shuhei Nakamura, 2nd Place Pro Tour Columbus 2004

- Creatures (16)

- 4 Blistering Firecat

- 4 Grim Lavamancer

- 4 Jackal Pup

- 4 Mogg Fanatic

- Instants (4)

- 4 Magma Jet

- Enchantments (4)

- 4 Seal of Fire

- Artifacts (4)

- 4 Cursed Scroll

- Lands (24)

- 8 Mountain

- 4 Bloodstained Mire

- 4 Rishadan Port

- 4 Wasteland

- 4 Wooded Foothills

- Sideboard (15)

- 4 Blood Oath

- 4 Ensnaring Bridge

- 3 Flametongue Kavu

- 3 Fledgling Dragon

- 1 Gamble

Hammer Regnier's ![]()

![]() Control deck from the first Pro Tour ever in 1996? Twenty-three lands.

Control deck from the first Pro Tour ever in 1996? Twenty-three lands.

U/W Control | Hammer Regnier

- Instants (20)

- 4 Counterspell

- 4 Disenchant

- 4 Power Sink

- 4 Spell Blast

- 4 Swords to Plowshares

- Sorceries (6)

- 1 Balance

- 1 Recall

- 4 Wrath of God

- Enchantments (3)

- 3 Land Tax

- Artifacts (8)

- 1 Ivory Tower

- 1 Zuran Orb

- 3 Icy Manipulator

- 3 Millstone

- Lands (23)

- 4 Island

- 6 Plains

- 1 City of Brass

- 1 Ruins of Trokair

- 3 Mishra's Factory

- 4 Adarkar Wastes

- 4 Svyelunite Temple

Seth Manfield's ![]()

![]() Vampires deck from the most recent Pioneer Pro Tour? Twenty-five lands.

Vampires deck from the most recent Pioneer Pro Tour? Twenty-five lands.

Rakdos Vampires | Pioneer | Seth Manfield, 1st Place Pro Tour Murders at Karlov Manor

- Creatures (14)

- 1 Sheoldred, the Apocalypse

- 2 Dusk Legion Zealot

- 3 Preacher of the Schism

- 4 Bloodtithe Harvester

- 4 Vein Ripper

- Planeswalkers (4)

- 4 Sorin, Imperious Bloodlord

- Instants (5)

- 1 Bitter Triumph

- 4 Fatal Push

- Sorceries (6)

- 2 Duress

- 4 Thoughtseize

- Enchantments (4)

- 4 Fable of the Mirror-Breaker // Reflection of Kiki-Jiki

- Artifacts (2)

- 2 Smuggler's Copter

Most folks play about twenty-four lands in Constructed, most of the time. Doesn't matter if you're Burn, Control, or Tribal.

Some decks play very few lands (some versions of StOmPy, most versions of Goblin Charbelcher decks); but a more interesting phenomenon is decks that play many, many lands (especially after sideboarding).

Mono-Blue Control | Randy Buehler, 12th Place World Championship Decks 1998

- Creatures (1)

- 1 Rainbow Efreet

- Instants (29)

- 1 Memory Lapse

- 2 Dissipate

- 3 Forbid

- 3 Mana Leak

- 4 Counterspell

- 4 Dismiss

- 4 Force Spike

- 4 Impulse

- 4 Whispers of the Muse

- Artifacts (4)

- 4 Nevinyrral's Disk

- Sideboard (15)

- 2 Capsize

- 1 Grindstone

- 4 Hydroblast

- 4 Sea Sprite

- 4 Wasteland

For Randy Buehler, adding more lands after sideboarding was an act of agency. He might typically do this in the mirror, where playing the first main phase spell could be a curtain call. Having more lands meant making more early game land drops, meaning he was less likely to be forced into action first.

That his extra lands were Wastelands meant that Randy could potentially limit his opponent's agency by creating a quasi-manascrew situation that limited their ability to make meaningful decisions. Being forced to make the first main phase play being, generally, a meaningfully bad decision, were they to make it.

Randy could transform his excess mana into card advantage via Whispers of the Muse despite such a high percentage of mana, mitigating mana flood. Or Capsize, which especially at 12+ mana, could be catastrophic.

In most other contexts having an extraordinarily high percentage of mana can result in flood loss in long games. Combo decks, by contrast, get around this by winning before the games go long enough for them to die of mana flood.

Prosperous Bloom | Mike Long, Pro Tour Paris 1997

- Instants (13)

- 1 Emerald Charm

- 1 Power Sink

- 1 Three Wishes

- 2 Memory Lapse

- 4 Impulse

- 4 Vampiric Tutor

- Sorceries (14)

- 1 Drain Life

- 1 Elven Cache

- 4 Infernal Contract

- 4 Natural Balance

- 4 Prosperity

- Enchantments (8)

- 4 Cadaverous Bloom

- 4 Squandered Resources

- Lands (25)

- 5 Island

- 6 Swamp

- 7 Forest

- 3 Bad River

- 4 Undiscovered Paradise

- Sideboard (15)

- 3 City of Solitude

- 4 Elephant Grass

- 1 Elven Cache

- 3 Emerald Charm

- 1 Memory Lapse

- 1 Power Sink

- 2 Wall of Roots

Mike Long's ProsBloom was the first competitive and successful Combo deck, winning Pro Tour Paris in 1997.

With 25 lands, Long was already at slightly more mana than average. But many of his cards - Natural Balance, Squandered Resources, and the namesake Cadaverous Bloom - did nothing but make more mana. Arguably he was 37/60 mana. Long could lose lots of ways... But rarely to flood as his deck could do kind of the opposite of Buehler's Whispers of the Muse: He could end the game as early as turn three, so it was rare he'd ever get to the point of flooding out.

But what do Buehler and Long have in common?

Both decks had agency over their draws. Any time you take an action, especially utilizing a card, to touch your library, you are making a decision; to that degree Mike's Bad River even counts! Often some topdeck control will have a meaningful impact on the outcome of the game. Randy might do something as innocuous as "burning" a Whispers of the Muse for ![]() just to hit his next land drop. Long might use Vampiric Tutor to find a missing combo piece that ends the game.

just to hit his next land drop. Long might use Vampiric Tutor to find a missing combo piece that ends the game.

The other side of this is a deck with, say, similarly high mana that doesn't have 1) good topdeck control, or 2) a good way to turn excess mana into more cards [i.e. mitigating the threat of mana flood]. Non-Blue Control decks sometimes fall into this category, which is one of the reasons they've been of dubious distinction, historically.

Is Agency Zero Sum?

This is a point Sam Black brought up in my Facebook group ("non-idiots").

I thought about it a little and I think the answer is not necessarily.

A land destruction deck with lots of cards like Wasteland, Rishadan Port, and various Stone Rains is probably making a lot of choices; some of which negatively impact the opponent's agency by reducing them to the classic position of manascrew. That would be a case where one deck's successful exercise of agency actively removes the other's access to agency.

But the Lost in the Woods example is a case where both decks have relatively little agency, especially if Lost in the Woods is on the battlefield already. One player is just revealing Forests (no meaningful decisions) and the other one might not make any decisions that impact the outcome of the game.

Conversely a long game between two Blue-White Control decks in Standard can exhibit lots of agency from both sides, with everyone touching their libraries constantly and a lot of thoughtfulness about threats and answers and the various routes to victory (Planeswalkers, utility land, deck damage, or the occasional creature) / how those might interact with the plethora of threats. Though I can't imagine many creatures living very long on either side.

The Four Quadrants of Agency

What point, if any, does this discussion of agency bring to anyone?

I think there are three takeaways. First we can look at four potential models for agency.

Quadrant One: Few Decisions / Low Impact

In caveman terms, this will correlate with low skill, or, again, at least low agency. This does NOT mean that a player who chooses a Quadrant One deck themselves is of low skill; rather that their deck is not, at least by comparison to Quadrant Three or Four decks, as conducive a vehicle to show off that skill relative to one with a lot of different kinds of cards and decisions.

A great example of this would be a contemporary White Weenie deck in an environment with lots of decks that, by their respective constructions, fall into the White Weenie deck's inherent features and strategies. The deck itself might have a high win expectation (and choosing it might therefore be ingenious); but from a game play perspective it's mostly just plopping dudes down at sorcery speed. Are there some decisions? Sure. "Some," I'm sure. But on a relative basis your power is in permanents (low skill) played at sorcery speed (low skill) and you mostly have to remember to attack and figure out how deeply you will play into removal.

Avatar Deck: Bo1 WW; CovertGoBlue circa September 2023

Bo1 White Weenie | CovertGoBlue

- Creatures (34)

- 2 Anointed Peacekeeper

- 2 Etraction Specialist

- 2 Skrelv, Defector Mite

- 4 Adeline, Resplendent Cathar

- 4 Coppercoat Vanguard

- 4 Hopeful Initiate

- 4 Intrepid Adversary

- 4 Lunarch Veteran // Luminous Phantom

- 4 Spellbook Vendor

- 4 Thalia, Guardian of Thraben

- Enchantments (4)

- 4 Ossification

- Lands (22)

- 20 Plains

- 1 Eiganjo, Seat of the Empire

- 1 Mishra's Foundry

I personally cleaned up on Arena with this build, which came to me via YouTube sensation CovertGoBlue. CGB, constantly frustrated with the prevalence of Mono-Red variants in Best-of-One Standard, wanted to make a deck that specifically preyed upon it: You'll note that it specifically doesn't play cards like Recruitment Officer, or some of the flashy threats that you might see in both other Mono-White Soldiers decks or the Player of the Year Blue-White builds.

In contemporary Magic, a lot of decision-making comes simply from how you spend your mana (or don't); and those kinds of cards do, in fact, complicate how a White Weenie deck might play; how much they are willing to risk to the board versus hold back; et cetera.

However here we see a deck that is mostly designed to accumulate power going wide; in such a way that it accumulates power going tall as a second order benefit. It specifically blunts the efficacy of direct damage simply by playing cards like Lunarch Veteran // Luminous Phantom instead of Recruitment Officer; and makes opposing spellcasting difficult with Thalia, Guardian of Thraben.

In bluntest terms, this deck, low agency by comparison, also grounds an opponent to lower agency by de facto manascrew and creating battlefield positions where even adept mechanics would be hard-pressed to attack and block profitably.

It is arguable that the act of choosing this particular Quadrant One deck is in fact a Quadrant Two decision. But moreover, the same deck might shift into another quadrant in another metagame. For instance in a metagame with a lot of competing creature combat (perhaps from other White Weenie decks?), your number of decisions (and hence agency) could skyrocket to Quadrant Three or even Quadrant Four with the same starting 60.

The takeaway here is that, like Who's the Beatdown? ... Categorizations like beatdown v. control (or low versus high agency) can shift depending on matchup or metagame. I do believe a deck like CGB's, which has approximately one-point-five effects that can act at instant speed (both lands) is less decision intensive than, say, the Avatar Deck of Quadrant Four.

I think you should generally play the deck most likely to win, but when two decks have similar expected value, you might choose this type if you think your opponents are on average better than you are, or if you want to conserve your mental energy for the Limited rounds.

Quadrant Two: Few Decisions / High Impact

Avatar Deck: Lost in the Woods; Jeremy Neeman, Pro Tour Dark Ascension

- 1 Lost in the Woods

- 40 Forest

Lost in the Woods is the best example, You don't make very many decisions, but the few ones you do make have a large impact. The first, and biggest, is just choosing to ball out with it. Certain all-in combo decks fall into this category as well. Lost in the Woods is atypical as a deck that goes to libraries, because every other example I can think of correlates to shorter games.

I would generally think about Quadrant Two very differently on a skill perspective than Quadrant One. You kind of make a very big gamble and sometimes get paid off. That's a different kind of skill than attacking and blocking. But again, if you're an A+ in-game mechanic, Quadrant Two is not where you'll get to best showcase your skills, because you make so few decisions.

Quadrant Three: Many Decisions / Low Impact

Quadrant Three decks tend to be very consistent. They also tend to play lots of turns (more turns, often, than Quadrant Four decks), so can be satisfying from the standpoint of both players getting to play a game of Magic. The Rock, Jund, and other mid-range decks - especially those with a wide variety of spells like Duress, Kolaghan's Command, or Pernicious Deed, that all do different things - are Quadrant Three.

Avatar Deck: Abzan Block; Patrick Chapin, Pro Tour Journey Into Nyx (winner)

Junk | Block Constructed | Patrick Chapin, 1st Place Pro Journey Into Nyx

- Creatures (18)

- 4 Courser of Kruphix

- 4 Fleecemane Lion

- 4 Sylvan Caryatid

- 2 Polukranos, World Eater

- 4 Brimaz, King of Oreskos

- Planeswalkers (4)

- 4 Elspeth, Sun's Champion

- Spells (13)

- 4 Hero's Downfall

- 4 Silence the Believers

- 1 Read the Bones

- 3 Thoughtseize

- 1 Banishing Light

- Lands (25)

- 2 Plains

- 3 Swamp

- 4 Forest

- 4 Mana Confluence

- 4 Temple of Malady

- 4 Temple of Plenty

- 4 Temple of Silence

- Sideboard (15)

- 1 Read the Bones

- 1 Thoughtseize

- 2 Arbor Colossus

- 1 Bile Blight

- 2 Boon Satyr

- 2 Deicide

- 2 Drown in Sorrow

- 1 Feast of Dreams

- 2 Glare of Heresy

- 1 Gods Willing

Some of the game's best players, including multiple Hall of Famers prefer this Quadrant. They make a lot of decisions, and every decision allows you to move closer to victory, after all.

Here Chapin built enormous consistency into a Block Constructed deck by maxing out on both mana-filtering Temples... and Mana Confluence. He could cast Fleecemane Lion on turn two and grind out card advantage with Courser of Kruphix over the course of the game. Other polychromatic Green players went with more linear card advantage strategies based around Eidolon of Blossoms, whereas Patrick strove to maximize his flexibility in a variety of situations - where he'd have interplay, even if he didn't start off with an overwhelming advantage or disadvantage - by mixing disruption, card drawing, efficient creatures... What we call "good stuff".

Notably he could be beatdown with Fleecemane Lion and Brimaz, King of Oreskos... Or he could play a mid-range control game plan by leveraging the comparatively high toughness of Courser of Kruphix... And Brimaz, King of Oreskos.

One of the reasons that this deck was so effective was that, being Block Constructed, the most powerful cards and effects were not wildly more powerful, as you'll see in Modern, Premodern, or Legacy. Elspeth, Sun's Champion might have been the most powerful non-linear thing anyone was doing in that tournament; meaning, Patrick's many decisions largely defied having their agency erased by opposing power level. At the same time, that same ceiling on power level - combined with the built-in value from so many individual cards - meant that relatively few were do or die for either mage.

Even a deck like Patrick's, which is about as Quadrant Three as you can imagine, can slide (or take its opponent) on that Who's the Beatdown?-esque continuum. The easiest example? Some decks just couldn't beat a Fleecemane Lion as Patrick positioned it. Hence, the potential impacts of their decisions might be reduced to low agency: They're going to lose to a 4/4 hexproof indestructible eventually, whether they concede now or they chump block five times before taking lethal damage.

Personally, I once started a Legacy Grand Prix with three byes, armed with the Patrick Sullivan Mono-Red deck. Our Hero later declared that he had won every match that he possibly could. Normally so handsome, he just happened to lose to a turn-one Iona, Shield of Emeria when playing for Day Two at 11pm, resulting in an atypical scowl. In many matches my understanding of the metagame, and in particular Red Deck mirrors, allowed me to eke out narrow wins despite playing a deck with only medium power level. In those matches, decisions had very high impact. For example, I refused to play a creature in the mirror when it was obvious my opponent was gripping 100 Searing effects, and this allowed me to win from two after three arduous turn cycles. However, against the Reanimator decks I faced, I was simply cooked before the game started; and more than once. It didn't matter how well I might have played in other circumstances; certain of my opponents' cards reduced my deck to low agency.

Decks with lots of card advantage (not necessarily cardboard advantage) will often fall into Quadrant Three, especially if it is all in the form of 1/1 tokens or one extra basic. While these decks often play high leverage cards, the presence of so much material can wash out the impact of many individual decisions. From Wingmate Roc to Zealous Conscripts, Sam Black is a master of designing into Quadrant Three.

Quadrant Four: Many Decisions / High Impact

Have you ever felt like you played a perfect game for say twenty turns, only to flub it all at the finish line?

Welcome to MichaelJ's longtime Magical kryptonite. This is the Quadrant where The Danger of Cool Things Lives. The absolute best players can get the absolute best results in this Quadrant; but for the rest of us it is probably more high variance than high expectation.

Depending on your matchups over the course of a day, mid-range decks (or decks that can masquerade as mid-range or control decks) will sometimes fall into this category.

Good players can get the most increment out of Quadrant Three and potentially Quadrant Four decks; but, again, what Quadrant a deck lives in is a completely different axis than how likely the deck is to win in the abstract.

Avatar Deck: The Cali Nightmare; Brian Selden, 1998 World Champion

Recurring Survival | Brian Selden, 1st Place Worlds 1998

- Creatures (24)

- 1 Cloudchaser Eagle

- 1 Man-o'-War

- 1 Orcish Settlers

- 1 Spike Weaver

- 1 Spirit of the Night

- 1 Thrull Surgeon

- 1 Tradewind Rider

- 1 Verdant Force

- 2 Nekrataal

- 2 Spike Feeder

- 2 Uktabi Orangutan

- 2 Wall of Roots

- 4 Birds of Paradise

- 4 Wall of Blossoms

- Instants (2)

- 2 Firestorm

- Sorceries (2)

- 2 Lobotomy

- Enchantments (8)

- 4 Recurring Nightmare

- 4 Survival of the Fittest

- Artifacts (2)

- 2 Scroll Rack

- Lands (22)

- 1 Swamp

- 8 Forest

- 1 Gemstone Mine

- 2 Karplusan Forest

- 2 Reflecting Pool

- 2 Underground River

- 2 Undiscovered Paradise

- 3 City of Brass

- 1 Volrath's Stronghold

- Sideboard (15)

- 1 Staunch Defenders

- 2 Pyroblast

- 2 Phyrexian Furnace

- 1 Hall of Gemstone

- 3 Emerald Charm

- 2 Dread of Night

- 4 Boil

I wanted to choose a Survival of the Fittest deck because those are the decks that have the most potential agency. If you have Survival in play you can do stack-stuff at basically any time. More recent, pre-Legacy bans, versions spat out Basking Rootwallas... Potentially during combat.

I further chose a deck from before the printing of Squee, Goblin Nabob; that also was not a combo deck. A cynical argument is that Survival decks aren't that decision-intensive: You just memorize different routines. But Selden didn't have Squee to help stockpile for his Scroll Rack and Firestorm.

What's the actual best answer to that creature? Man-o'-War or Nekrataal? Or is it Tradewind Rider? Should I search up and discard creatures I don't ever want to draw? Or should I leave them in my deck for future Survival fuel? That's lots and lots of decisions on almost every stack; some of which are extraordinarily high impact (being a specialized, built-in, two-for-one).

The Agency Everybody Has

We think of agency, I think of agency anyway, mostly in Constructed terms. But obviously everyone has a lot of agency when playing Limited (at least unless they're up against Lost in the Woods).

The core engine of Limited Magic - creature combat - is an unbending agency-fest; in particular on defense. In Magic, you get to pick when to attack, and with what creatures... But the defending player has the last word about who gets through unblocked and how good combat is going to be for everyone.

Manascrew and mana flood are still things in Limited, but it's far less likely you'll be bowled over by a Fable of the Mirror-Breaker // Reflection of Kiki-Jiki or buried under a three consecutive Wedding Announcement // Wedding Festivitys if only because they're rare cards.

As we said, agency as I envision it stretches across lots of Magic categories. It's wherever you make a decision and that decision has impact (or doesn't, or doesn't). This can be in strategies, deck selection, draw quality, or creature combat. It can also just be on the stack.

Fact or Fiction, as a single card, is probably the greatest instantaneous expression of agency, ever.

Defending players get to set the rules. Maybe not against a five-spell FoF... But generally they can create paradigms that deny removal, give up card types that are easy to ignore, or keep the Blue mage tight on lands despite drawing three extra cards.

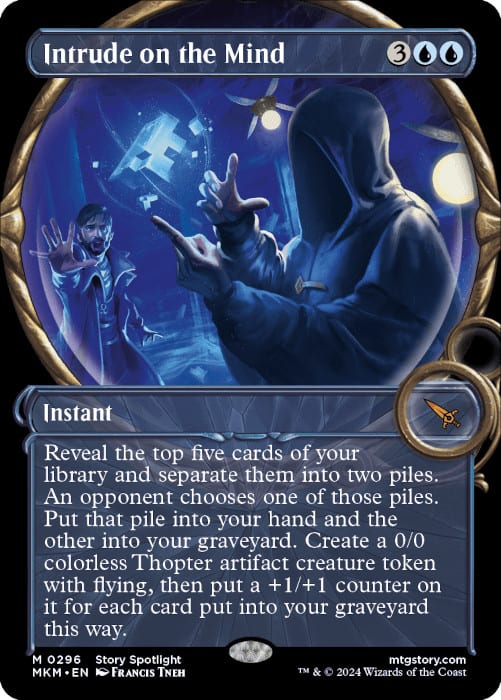

Intrude on the Mind is probably a little less high-agency; but it's still agency.

At least you can pick how big their Thopter will be.

LOVE

MIKE