Two weeks ago, I wrote a little about velocity. I want to expand on that subject in today’s article and discuss how you can limit your opponent’s ability to generate velocity. There are two basic things that you need to understand:

- How is my opponent generating velocity?

- How do I counter my opponent’s ability to generate velocity?

This article serves as a follow-up to my article two weeks ago in the sense that here I intend to discuss the practical applications and implications of the principles I put forth in my previous article.

Getting the Obvious Out of the Way

Killing your opponent first is always an option.

There—that’s now officially out of the way. No matter what kind of velocity your opponent is relying on, you can attempt to kill him before it gets online. The big thing to realize about velocity is that it never kills your right away. The velocity player requires some measure of time from when he begins building velocity to when he is able to convert it into some tangible advantage or victory. For some velocity decks (such as storm combo), that window is very short. For other decks, it is quite long. Either way, you can attempt to kill the velocity player before that window opens or during that window.

What I want to focus on is the ability to deny the velocity player his velocity. Strategically, this puts you in a better position because the location of the attack is better. If you simply try to kill your opponent but fail, you will ultimately be overwhelmed. However, if you attack his velocity, not only do you present the possibility of outright winning the game, but because you attack his primary avenue of offensive play, you make it very difficult for your opponent to counterattack in any meaningful capacity.

So, let’s look at denying velocity.

Three Kinds of Velocity

There are three primary ways by which decks generate velocity. They are as follows:

- Mass something

- Base your velocity on a single-card foundation

- Create a web of intersecting synergies

Identifying which of these plans your opponent is on is crucial to attacking his velocity—you attack each of these plans in a different manner. First, we’ll examine how each of these plans generates velocity, and then we’ll talk about attacking them.

Amassing Resources

This is the easiest of the three plans to recognize. Decks that win with this plan amass a specific resource and aim to exploit the momentum that resource generates to win the game. The most evident examples of this are the lords for various creature types. However, other groups of cards can have similar effects as well (for example, the Honden cycle from Champions of Kamigawa block or the Sanctuary cycle from Invasion block). Legacy holds two good examples of this: Merfolk and Enchantress.

"Merfolk by Sam Kuprewicz (Fifth at SCG: Indianapolis, October 2, 2011)"

- Creatures (24)

- 2 Phantasmal Image

- 4 Coralhelm Commander

- 4 Cursecatcher

- 4 Lord of Atlantis

- 4 Merrow Reejerey

- 4 Silvergill Adept

- 2 Kira, Great Glass-Spinner

- Spells (15)

- 3 Dismember

- 4 Daze

- 4 Force of Will

- 4 Aether Vial

- Lands (21)

- 3 Island

- 1 Flooded Strand

- 1 Mishra's Factory

- 4 Mutavault

- 4 Polluted Delta

- 4 Underground Sea

- 4 Wasteland

- Sideboard (15)

- 2 Relic of Progenitus

- 2 Chains of Mephistopheles

- 3 Flusterstorm

- 1 Go for the Throat

- 3 Submerge

- 2 Perish

- 2 Tower of the Magistrate

"Enchantress by Chris Smith (Fifth at SCG: Tampa, March 4, 2012)"

- Creatures (5)

- 4 Argothian Enchantress

- 1 Emrakul, the Aeons Torn

- Spells (36)

- 4 Enlightened Tutor

- 1 Replenish

- 1 Blood Moon

- 1 Energy Field

- 1 Illusions of Grandeur

- 1 Moat

- 1 Puca's Mischief

- 1 Sigil of the Empty Throne

- 1 Wheel of Sun and Moon

- 2 Oblivion Ring

- 2 Solitary Confinement

- 4 Elephant Grass

- 4 Enchantress's Presence

- 4 Sterling Grove

- 4 Utopia Sprawl

- 4 Wild Growth

- Lands (19)

- 3 Plains

- 4 Forest

- 1 Taiga

- 1 Tropical Island

- 2 Horizon Canopy

- 2 Savannah

- 4 Windswept Heath

- 2 Serra's Sanctum

- Sideboard (15)

- 1 Pithing Needle

- 1 Baneslayer Angel

- 1 Choke

- 1 City of Solitude

- 1 Ground Seal

- 1 Oblivion Ring

- 1 Seal of Primordium

- 1 Solitary Confinement

- 1 Stony Silence

- 2 Replenish

- 4 Leyline of Sanctity

Merfolk gains advantage and velocity by amassing its lords. Between Merrow Reejerey, Lord of Atlantis, Coralhelm Commander, and Phantasmal Image, Merfolk had access to fourteen individual lords to try to generate a substantial board presence. The Merfolk deck relies heavily on generating a critical mass of lords (usually somewhere between two and four) because its other creatures don’t do much from an offensive standpoint, having only 1 or 2 power naturally. The offensive explosiveness and punch of the deck lies exclusively in the lords.

The Enchantress deck wins by amassing enchantress effects so that it can draw a ton of cards for each enchantment it plays. Between Argothian Enchantress, Enchantress's Presence, Sterling Grove, and Enlightened Tutor, Enchantress has sixteen ways of accessing enchantress effects while only needing two on the board to really get going. The rest of the deck is focused on denying your opponent options and constricting his ability to attack you. Enchantress requires very few actual win conditions (there is only one Sigil and one Emrakul to end the game) because not only can it search for its win conditions, but it can simply generate an overwhelming advantage and then win at its leisure.

When a deck seeks to win by amassing any given resource, the logical course of action would be to attempt to deny it that resource. That does seem correct. However, because the strategy is amassing that particular resource, you don’t actually have to completely deny it. You simply have to deny it enough that you can keep up with the opponent’s velocity with an advantage in some other area. Letting Merfolk have a lord or two or letting Enchantress have a single enchantress effect isn’t the end of the world. Sure, you should do your best to deny it if it’s profitable, but you still have to advance your game plan in other areas as well.

The key feature to be aware of with this sort of strategy is the high degree of redundancy built in. This means that decks that rely on this sort of velocity generation either don’t have a backup plan or have a very weak one. Simply put, decks that do this devote a ton of space to redundancy to be able to generate velocity in an appropriate manner. Often, these decks devote nearly half of their nonland spells to do so. The other half needs to include typical defensive countermeasures as well as spells to help support their primary game plans. That doesn’t leave much room for backup plans. This is a key feature of decks like this. If you can cut off Plan A by sufficiently denying velocity, these decks frequently just fall flat on their faces.

Relying on a Lynchpin

The second method of generating velocity relies on a specific card—the lynchpin of the strategy. Decks that use this method rely on their lynchpins as the basis of the velocity they generate. This occurs in one of two ways: Either the entire deck is centered on that card, or that card exists in a specific space such that it synergizes with every element of the deck, thus forming the foundation of the synergistic evolution of the deck.

Recently, we’ve had two very good lynchpin strategies show up in Standard: Valakut and Faeries. Valakut is a lynchpin deck built around a single card: Valakut, the Molten Pinnacle. The entire deck is centered on abusing the card and invoking as many triggers as possible. Remove Valakut, and the Valakut deck is almost completely toothless.

Faeries, on the other hand, was a much more balanced strategy. Faeries could very well operate without Bitterblossom, but the deck was a completely different animal with Rebecca’s 2-mana enchantment in play. This is because all of the synergistic elements of the deck were exponentially more powerful with a Bitterblossom in play. Bitterblossom provided tokens, which made Scion of Oona more powerful, enabled Spellstutter Sprite to counter pretty much everything, and ensured that your Mistbind Clique always had something to champion. Bitterblossom also served as both an offensive and defensive measure, allowing the deck to take its control-aggro stance and transition from defense to offense and back seamlessly. Faeries was strong without Bitterblossom, but it was an absolute monster with it in play.

This Faeries list is by Yuuta Takahashi and; and the Valakut list . . . well, how could I resist using one from the most famous wielder of Explore?

"Faeries by Yuuta Takahashi (First at Grand Prix: Shizuoka, 2008)"

- Creatures (19)

- 3 Sower of Temptation

- 4 Mistbind Clique

- 4 Pestermite

- 4 Scion of Oona

- 4 Spellstutter Sprite

- Spells (16)

- 4 Cryptic Command

- 4 Nameless Inversion

- 4 Ancestral Vision

- 4 Bitterblossom

- Lands (25)

- 3 Faerie Conclave

- 4 Mutavault

- 4 River of Tears

- 4 Secluded Glen

- 4 Underground River

- 2 Snow-Covered Swamp

- 4 Snow-Covered Island

- Sideboard (15)

- 4 Bottle Gnomes

- 4 Deathmark

- 2 Familiar's Ruse

- 2 Razormane Masticore

- 3 Thoughtseize

"Valakut by Alex Bertoncini (Top 16 at TCGplayer event NYC)"

- Creatures (14)

- 2 Avenger of Zendikar

- 2 Inferno Titan

- 4 Overgrown Battlement

- 4 Primeval Titan

- 2 Wurmcoil Engine

- Spells (19)

- 3 Summoning Trap

- 4 Lightning Bolt

- 2 Growth Spasm

- 3 Cultivate

- 4 Explore

- 3 Khalni Heart Expedition

- Lands (27)

- 11 Mountain

- 6 Forest

- 3 Evolving Wilds

- 3 Terramorphic Expanse

- 4 Valakut, the Molten Pinnacle

- Sideboard (15)

- 2 Acidic Slime

- 1 Avenger of Zendikar

- 1 Burst Lightning

- 3 Gaea's Revenge

- 4 Obstinate Baloth

- 4 Pyroclasm

When attacking a deck like this, the most efficient course of action is normally to go after whatever lynchpin the deck has. Denial of the use of a most critical card neuters the deck fairly well. The best position to be in is, of course, to make the best card a liability, but this isn’t always possible. It is, however, always possible to attack the best card in some way, shape, or form.

In many ways, this is similar to how you attack a deck that tries to amass resources. However, because you are attacking a single card, you often have other strategic avenues open to you. Bitterblossom is a great example of this. Let’s look at some examples of some cards that would be useful for attacking Bitterblossom: Curse of Death's Hold, Aether Flash, Engineered Plague, Engineered Explosives, Pernicious Deed, Ratchet Bomb, enchantment removal with other functions (such as Esper Charm). Cards like these are all great examples of ways of attacking the card directly.

That isn’t the only way of attacking Bitterblossom, though. Perhaps the most effective means of attacking Bitterblossom is represented by this card: Lightning Bolt. Facing a high degree of aggression backed by reach turns Bitterblossom into a liability, putting Faeries in an awful position. This was evident in the Zoo-versus-Faeries matchup in Extended. It was a bad matchup even with Umezawa's Jitte. Without it (a card that Standard Faeries never had access to), the matchup is very, very difficult for the Fae player.

The key thing to note here is that you can attack a single card both strategically and tactically in an effective manner. This is the central element of reducing the velocity of your opponent. By attackingan opponent’s core cards, you can often put him in unpleasant situations.

There is a second, important thing to remember about this strategy, however: backup plans do exist. Because decks relying on lynchpins only have to devote four slots to it, they often have room for some manner of Plan B (Faeries still worked without Bitterblossom, and Valakut had things like Avenger of Zendikar, Summoning Trap, Inferno Titan, and Wurmcoil Engine). This varies in strength from mediocre to rather strong, but you have to be aware it exists. However, dealing with a succession of Plan Bs is much easier to deal with than primary game plans, and if you reach that situation, you should already be advantaged.

Caught in a Web

Decks that rely on this method of velocity produce advantage by taking individually strong cards and/or synergies and binding them together through additional synergies. Two examples are below: Vengevine Survival and Cunning Wake.

"Vengevine Survival by Nick Spagnolo (First at SCG: Charlotte, October 31, 2010)"

- Creatures (25)

- 1 Eternal Witness

- 1 Quirion Ranger

- 1 Trygon Predator

- 1 Waterfront Bouncer

- 1 Wonder

- 3 Basking Rootwalla

- 4 Fauna Shaman

- 4 Noble Hierarch

- 4 Trinket Mage

- 4 Vengevine

- 1 Shield Sphere

- Spells (14)

- 1 Daze

- 1 Spell Pierce

- 1 Spell Snare

- 4 Force of Will

- 4 Survival of the Fittest

- 1 Brittle Effigy

- 1 Lion's Eye Diamond

- 1 Pithing Needle

- Lands (21)

- 1 Island

- 5 Forest

- 2 Wasteland

- 3 Verdant Catacombs

- 4 Misty Rainforest

- 4 Tropical Island

- 1 Gaea's Cradle

- 1 Tree of Tales

- Sideboard (15)

- 1 Basilisk Collar

- 1 Tormod's Crypt

- 1 Faerie Macabre

- 1 Gilded Drake

- 3 Krosan Grip

- 2 Spell Pierce

- 4 Submerge

- 1 Emrakul, the Aeons Torn

- 1 Llawan, Cephalid Empress

"Cunning Wake by Daniel Zink (2003 World Champion)"

- Spells (33)

- 1 Circular Logic

- 2 Vengeful Dreams

- 3 Cunning Wish

- 3 Moment's Peace

- 3 Renewed Faith

- 4 Mana Leak

- 2 Decree of Justice

- 4 Deep Analysis

- 4 Wrath of God

- 3 Compulsion

- 3 Mirari's Wake

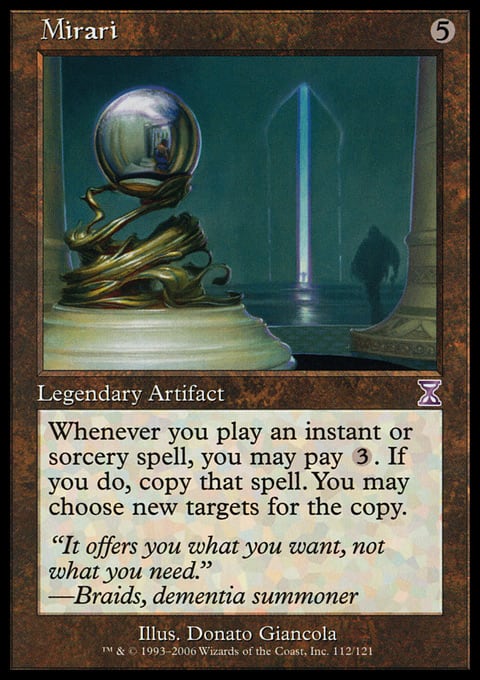

- 1 Mirari

- Lands (27)

- 4 Forest

- 4 Plains

- 7 Island

- 2 Elfhame Palace

- 2 Flooded Strand

- 4 Krosan Verge

- 4 Skycloud Expanse

- Sideboard (15)

- 3 Anurid Brushhopper

- 1 Circular Logic

- 2 Exalted Angel

- 1 Hunting Pack

- 1 Krosan Reclamation

- 1 Ray of Distortion

- 3 Ray of Revelation

- 1 Renewed Faith

- 1 Vengeful Dreams

- 1 Wing Shards

So, how does this concept of intersecting supports work? Let’s examine both of these decks. We’ll start with Vengevine Survival.

Vengevine Survival is built on the following core interactions:

- Vengevine with Survival of the Fittest or Fauna Shaman

- Basking Rootwalla with Survival of the Fittest or Fauna Shaman

- Vengevine with 1-drop green creatures

- Vengevine with Trinket Mage and Shield Sphere

Many of the interactions support each other in different ways as well. For example, the 1-drop green creatures of choice are Basking Rootwalla (which supports Survival of the Fittest), Quirion Ranger (which untaps Fauna Shaman), and Noble Hierarch (which accelerates you into Vengevine, Survival, or Fauna Shaman and provides mana to activate the latter two). Essentially, many cards serve multiple functions within different interactions, allowing the deck to have its fingers in multiple proverbial pies. Vengevine Survival is a good example of taking multiple small synergies and binding them into a larger synergy.

Now let’s look at Cunning Wake. Before we begin, it’s important to note that Cunning Wake was played under Classic Sixth Edition (but not M10) rules. The most relevant part of these rules was that Wishes could retrieve both cards in the sideboard and any card in the exiled zone. Cunning Wake was built around the following three cards:

|

These three cards form the backbone of the deck, and each does wonderful things individually. The deck was built to take advantage of each of these cards individually. It had a lot of instants to find with Cunning Wish, and what wasn’t an instant was a sorcery, so there were a ton of things to fork with Mirari. It could also take great advantage of the mana generated by Mirari's Wake. Playing Compulsion and Deep Analysis as a draw engine alongside expensive spells like Decree of Justice and Exalted Angel was not cheap, and Mirari's Wake provided the mana to power it all. However, when you started combining them, you began to see the synergies evolve. The primary synergy was the fact that Mirari allowed you to fork Cunning Wish, which meant that one Cunning Wish could find you a previously used Cunning Wish and another spell; Mirari's Wake then became the mana engine that powered the combination of Mirari and Cunning Wish.

So, how do you go about attacking a deck like this? In general, the best strategy is to simply try to cut off access at one point in particular. Frequently, it is best to ignore one piece of the web and devote all your attention to strangling a particular resource or card. You could, for example, against Vengevine Survival, attempt to focus on cutting off the graveyard, forcing the deck into a more normal beatdown plan. Against Wake, the plan is to choke the deck on mana, and thus attack Mirari's Wake. There is some splash damage on Mirari and Cunning Wish in this respect, but the primary focus on Wake is the best approach.

Attacking a web-like group of synergies in this manner is actually quite difficult. Even so, it’s still often the most effective means of hampering a deck that creates these supporting synergies. In essence, it is like trying to cut off one leg of a multi-legged creature. If you have limited resources, focusing your energy like this is probably the best means of slowing it down.

The thing to note here is that it’s very difficult, if not impossible, to stop a deck like this from generating any velocity at all. It’s also important to note that decks that rely on this strategy tend to have a high degree of inertia as well. Therefore, decks that can create this strong web of synergies are often extremely powerful and can easily dominate formats. After all, if they can generate both strong velocity and good inertia, they have high momentum, and are thus well capable of winning lots of games.

As a player facing strategies like this, the best you can do is hope to hinder your opponent enough that you can overpower him in some other area. This means that you can’t abandon your primary game plan, and you have to find a way of generating a focused attack on some area of the opponent’s game plan. This places huge strategic and tactical constraints on your options, forcing you into an uncomfortable position. This is an additional reason that web-based velocity is so powerful: It is difficult for the opponent to attack it profitably.

All in all, this sort of velocity is by far the most dangerous.

Conclusion

Most uses of velocity fall into one of these three types or a combination thereof. By identifying how your opponent is attempting to generate his velocity, you also identify the proper avenue of attack. Knowing this avenue is crucial for constructing both your maindeck and your sideboard to defeat an expected velocity-wielding foe.

As an exercise in looking at what happens when a deck is capable of generating too much velocity too quickly, look at arguably the most dominant Standard deck of all time: Affinity.

"Go Anan Affinity by Shuuhei Nakamura (Japanese Nationals 2004)"

- Creatures (20)

- 4 Disciple of the Vault

- 4 Arcbound Ravager

- 4 Arcbound Worker

- 4 Frogmite

- 4 Myr Enforcer

- Spells (22)

- 2 Electrostatic Bolt

- 4 Shrapnel Blast

- 4 Thoughtcast

- 4 Chromatic Sphere

- 4 Skullclamp

- 4 Welding Jar

- Lands (18)

- 2 Blinkmoth Nexus

- 3 Glimmervoid

- 3 Darksteel Citadel

- 3 Seat of the Synod

- 3 Vault of Whispers

- 4 Great Furnace

"Vial Affinity by Brian Kibler (Top 4 at GP: New Jersey, 2004)"

- Creatures (25)

- 2 Atog

- 2 Moriok Rigger

- 4 Disciple of the Vault

- 2 Myr Retriever

- 3 Myr Enforcer

- 4 Arcbound Ravager

- 4 Arcbound Worker

- 4 Frogmite

- Spells (15)

- 4 Thoughtcast

- 3 Cranial Plating

- 4 Aether Vial

- 4 Chromatic Sphere

- Lands (20)

- 1 Glimmervoid

- 4 Blinkmoth Nexus

- 3 Great Furnace

- 4 Darksteel Citadel

- 4 Seat of the Synod

- 4 Vault of Whispers

"Plating Affinity by Gabriel Nassif (Top 8 at Worlds 2004)"

- Creatures (22)

- 2 Somber Hoverguard

- 4 Disciple of the Vault

- 4 Arcbound Ravager

- 4 Arcbound Worker

- 4 Frogmite

- 4 Ornithopter

- Spells (20)

- 4 Shrapnel Blast

- 4 Thoughtcast

- 4 Chrome Mox

- 4 Cranial Plating

- 4 Welding Jar

- Lands (18)

- 3 Blinkmoth Nexus

- 3 Glimmervoid

- 4 Great Furnace

- 4 Seat of the Synod

- 4 Vault of Whispers

Just look at the velocity that Affinity was capable of generating compared to its peers, and you’ll see why the deck was so incredibly powerful. It generated far too much velocity extremely quickly and would literally just run people over.

Why don’t you take a look and see how you would fight the menace?

But, before you begin, here’s a note on card legality:

Skullclamp was banned in June 2004, coinciding with the release of Fifth Dawn. Arcbound Ravager, Disciple of the Vault, and the six artifact lands (Darksteel Citadel included) were banned in June 2005, coinciding with the release of Saviors of Kamigawa. Keep that in mind as you look in Onslaught block, Mirrodin block, Kamigawa block, and Eighth Edition for answers.

Chingsung Chang

Conelead most everywhere and on MTGO

Khan32k5 at gmail dot com