Welcome back to World Building 101! Last week, I shared some of my favorite ways to go about developing Magic worlds, and it sparked some good discussion in the comments. This week, and going forward, I’m going to explore these methods one at a time and showcase some results. That means that we’re going to end up with a lot more card designs going forward, so it’s disclaimer time:

With that out of the way, this week, we’ll begin with the most straightforward and least fruitful method that I explained last week: building Magic sets in an existing world. I’ll mostly stick to well-known stories so that the process is evident, but since most of us don’t read about Magic worlds before playing their sets, I’ll include some more obscure worlds since the cards ought to stand on their own. Also, don’t expect to see cards of all your favorite characters; as I mentioned last week, trading card games are a poor medium for transmitting linear stories, so while there will be wizards from J.K. Rowling’s universe, Harry Potter himself need not appear.

Harry Potter

As a somewhat generic fantasy setting (once you get into the parts of the world that are magical)—and an incredibly well-known one—J.K. Rowling’s universe is an ideal place to start our discussion. Let’s begin with some top-down depictions of elements from this world and see where they lead us.

Probably because of Innistrad, I started by thinking about curses. Cursing players is awesome, and I think it was the right choice. That said, this choice highlights one of the numerous pitfalls of designing into a world you can’t change. If we were to set a block in Harry Potter Land, it would be pretty strange not to include the three unforgiveable curses, but Imperio, the mind control curse, doesn’t work so well as an enchant player. Who wants Curse of Mindslaver? It does, however, work well as some sort of Control Magic effect. Similarly, while Avada Kedavra could be done as a Door to Nothingness, it’s probably better off as a Terminate. Both Persuasion and Terror are staples of Magic, so some sort of twist is in order. Let’s look then to Crucio—a spell for torture. The first place I thought to look was, well, Torture.

Mark Rosewater talked about how Lorwyn started with -1/-1 counters in an attempt to avoid death but that the mechanic ended up feeling like torturing the creatures rather than mercifully ending their lives, and the mechanic was promptly moved to Shadowmoor. If -1/-1 counters felt that way in Lorwyn’s pastoral setting, we probably wouldn’t have too much trouble evoking that feeling here, but there’s some question as to whether this block would have enough torture going on to make -1/-1 counters our creature counters of choice. Perhaps we can incorporate a few bloody quills.

Setting that issue aside for a moment, the Harry Potter series makes extensive use of magic for combat, which is a great fit for Limited (and increasingly, Constructed) Magic. I chose to make curses trigger when the affected creature enters the fray, but they could easily work as more conventional Auras.

|

|

If we followed this path, we’d want some Taunts to help them function. Note that this design of Imperius Curse doesn’t take a creature on its own, but it is more of a Pacifism. We don’t want cards not to do what they say—even if it makes for cool Draft archetypes—but this might be okay if we included creatures with strong enough attack triggers to make people play into the Mind Control . . . On second thought, that probably just leads to an escalation in power level.

The other angle is to make these somehow feel unforgiveable—perhaps something like:

|

|

Regardless of curse design, the Harry Potter universe has innumerable other possibilities to explore, but not all of them work as cleanly as one would like. Take for instance apparating:

|

|

Of course, this isn’t the only option—Magic has represented teleportation with unblockbility (Teleport) and bounce (Blinking Spirit), but I’m not looking to have a Limited environment in which nobody ever blocks, and returning to hand doesn’t feel as much like teleportation to me. That said, if you look at how much text this ability takes, it becomes evident that all the cool reusable enters-the-battlefield triggers we might want will be hard to jam onto non-rares. Immediate blinking is slightly cleaner, but it’s still awfully complex for a capability as commonplace as having a driver’s license.

I’m sure I could fill this column just writing about a Magic design of Harry Potter for years to come, but let’s move on to something else to get some perspective.

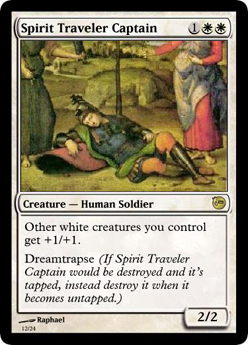

Chrestomanci

Moving to Diana Wynne Jones’ Chrestomanci series, we find some more novel Magic to play around with. Christopher Chant is introduced to the reader not as the Chrestomanci, but as a Spirit Traveler. What does that mean? Let’s see if the cards can speak for themselves:

|

|

Not quite? Spirit travelers are beings who can move between the numerous different worlds in this universe in their sleep. In The Lives of Christopher Chant, in which the protagonist has nine lives, he dies in dreams, and then has similar circumstances lead to his death after he’s woken up. For instance, he’s stabbed in a dream, and the next day, a curtain bar falls and impales him.

Unfortunately, it’s hard to give players the impression they’re in a dream since all the worlds of Magic are, by their natures, fantastical. I’m sure there’s a reasonable execution, but the proxy of watching your creatures sleep sure isn’t too interesting.

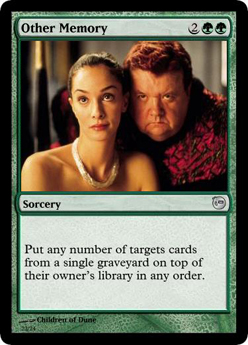

Dune

While Magic is obviously based in the realm of fantasy, Mirrodin has shown the game’s potential to work with flavor that’s a bit farther afield. Frank Herbert’s masterwork is a piece of science fiction, but the story centers a lot more around the strange powers that people possess than their technological superiority. Most of aristocratic lifestyle is lived in the future: anticipating assassinations, using the Spice to find safe space routes, tracing the consequences of diplomatic decisions, and planning succession to facilitate understanding of human nature at the very deepest level. Strong tournament players already play Magic this way, anticipating their opponents’ moves and figuring out how they plan to finish games as they decide mulligans. The majority of players, however, do not. It’s entirely possible that trying to build this sort of gameplay into Limited would result in the same chessiness that we saw in Standard Caw-Blade mirrors, but if there were a lot of ways to help players derive the information they needed, it might be doable.

In a block full of cards like Atreides Mentat, weaker players would need some help.

|

|

Here, we’re starting to discover to an important point. Emulating a world with individual cards isn’t terribly interesting. To really put your setting to use, you want to give players a taste of being in that world. It could be small, like the mechanical feel of Mirrodin’s Equipment and modular creatures, or it could be the whole point, like Innistrad’s horror setting, but somehow, the gameplay itself ought to convey what your world is all about. And unfortunately, as far as I can tell, neither Harry Potter nor The Lives of Christopher Chant is “all about” anything.

Eragon

Christopher Paolini’s Inheritance series brings us to another more or less conventional fantasy setting, but this author introduces fewer memorable feats of spellcraft and instead fills his world with a multitude of interesting beings. We’re back to a series that lacks the environmental focus that’s so helpful for a Magic setting, but we’ve got another lesson to learn. Early on, the reader encounters Galbatorix’s assassins, the Ra’zac:

They’re stronger than humans, and that feel is easiest to convey by shirking the normal guidelines for humanoid size in terms of power and toughness. Enter Ra’zac Trackers. Of course, this sort of design does little to define our new race. That doesn’t mean it’s useless, but it’s more of an Amphin Cutthroat than an Illusionary Servant. Later on, the reader learns that the Ra’zac can’t be detected by magic, but trying to show this realization in a TCG would make players think that the Ra’zac gained a new power—not that they’d been capable of it all along. The more sensible route is then to find stories that are more about exciting changes than exciting realizations.

Moving Beyond

This exercise has certainly led me to some new insights about Magic design, but it’s also reinforced my conviction that the game will never fit snugly into an existing story. Magic makes a lot of demands upon a world, and you would be hard pressed to find a world that fulfills them all. There are some—worlds with stories so deep that you could dredge up anything you might ever need for a Magic set. But picking a familiar setting encourages the audience to use its foreknowledge, and as such, the audience will expect to see the central pieces of that setting. That is, people will expect too many familiar faces to make plausible outside of a Kamigawa-esque legend fest. But I’m getting ahead of myself; we’ll have plenty of time to discuss meeting expectations next week when we move on to wider genres.

Until then, feel free to try your hand at defining your favorite worlds in Magic terms and to post the results below.

Jules Robins

Julesdrobins at gmail dot com