Magic Hall of Fame (HoF) season has ignited a discussion about slow play, with allegations of intentional stalling tarnishing a time that should be a celebration of the best in the game. I thought I would dig into some of the statistics to see if slower Magic players gain an advantage in matches that go to time. The results, as they say, might surprise you.

Part of what makes this subject particularly exasperating is that it is in many ways inherently subjective. Whether or not a player is intentionally stalling his opponent, or merely honestly playing out a very complicated board, is nearly impossible to discern from the outside.

That said, on the recent Pro Points Podcast, Paulo Vitor Dama da Rosa made a very good point that at once explained how players who play slowly can both be completely guiltless and still put others in an unfair situation. His point, which I'll call "PV's Theory of Good Faith Slow Play," (Or PVToGFSP, because I like pointless acronyms) I will paraphrase below, with apologies to PV for putting words in his mouth in an attempt to summarize:

I appreciate PVToGFSP because it assumes good faith yet identifies how someone acting honestly and even fairly can create an unfair situation. So as a theory it intuitively sounds good, but is it true? Well we have the match results - we can check for ourselves.

Forensic Statistics

It's possible to detect cheating or otherwise unfair play through statistics. Most famous was the statistical analysis of sumo matches Steven Levitt and Stephen Dubner conducted in Freaknomics. Levitt and Dubner, purely based on analysis of unusually high win rates, implied that wrestlers were fixing games in matches where one wrestler had a much higher incentive to win than the other... an accusation that was later proved correct when a massive sumo win-trading scandal came to light.

We'll do something similar today, where our goal is not necessarily to detect cheating per se, but simply to test if PVToGFSP is true and slower players are accruing an unfair advantage in matches that run out of time. Magic matches are best of three, so a match that concluded in time should result in a 2-1 or 2-0 win for one player on the reported results. If a match ran out of time, we should see that reported as 1-0 win, 1-1 draw, or 0-1 loss on a player's result record.

Understanding this, let's look at two players that are known for having a slower, more deliberate pace of play, Seth Manfield and Gabriel Nassif. Manfield is a potential HoFer whose candidacy this year has created conversations about slow play, and Nassif is an inducted HoFer whose deliberate pace of play is so sluggish to be a frequent subject of jokes on coverage. We will test the following claims and see if they hold true:

Going into this analysis and without having first looked at the numbers, I am near-certain that claim (I) will be true, even if by itself that doesn't necessarily say anything. Slower players will obviously run out of time and draw more matches, but unfortunately, purely from the results, it can be difficult to determine if a draw was actually a good outcome for the player (IE, they would have lost had the game reached its conclusion, or a draw locked them for a certain threshold in the tournament) or a bad outcome for that player. I think it's more likely than not that claim (II) is true, because PVToGFSP is so intuitively appealing and it just seems to stand to reason that if you are a slower player you will find yourself in more spots where you can leverage the clock to your advantage.

The Data

Let's set a baseline first. The source I'm using is the amazing www.mtgeloproject.net, which has comprehensive results from PTs and GPs that go back decades. Unfortunately there's no easy way to aggregate multiple players' records in mtgeloproject, so I will select some players as a baseline to compare against, including Shota Yasooka, Luis Scott-Vargas, Owen Turtenwald, and the man who inspired this whole investigation, PVDR himself. In choosing a baseline, I basically tried to pull up all the players on MTGELOproject's leaderboards with a long list of match results on record (>1500 GP/PT-level matches) to give us a better sample size.

We'll start by using Shota Yasooka to illustrate the methodology, and then I'll summarize the results. Yasooka is an interesting example as he's known as an efficient, brisk player even though he favors control decks, which tend to take more time to pilot. Yasooka's combined GP and PT record is 1066-644-42, for a 62.3% non-draw win rate. On his player page, we find that Yasooka had non-intentional draws in 18 matches, won just one game that went to time 1-0, and lost two games that went to time 0-1, for a measly win rate in games that go to time of 33%, but on a completely meaningless sample size of three.

With a total of 21 matches that went to time, 1065 wins that completed in time, 642 losses that completed in time, and the remaining draws being intentional draws, Yasooka ran out of time in about 1.2% of his matches. Notably if we study Yasooka's history we also find that far more matches ran out of time early in his career: 13/18 of his draws that went to time occurred in the first half of his career and only 5/18 in the second half. This makes sense as even an all-time great such as Shota Yasooka needed time and experience to become the master of control decks that he's known for being today.

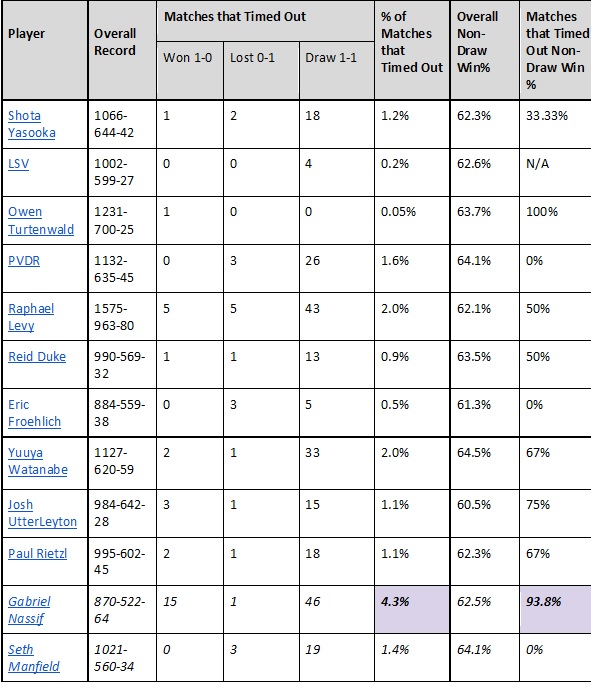

Let's summarize the numbers for the remaining players in our baseline, and compare our baseline players against Gabriel Nassif and Seth Manfield in italics, highlighting any significant deviations. All data is as of August 27, 2018.

(Links: Shota Yasooka, LSV, Owen Turtenwald, PVDR, Raphael Levy, Reid Duke, Eric Froehlich, Yuuya Watanabe, Josh UtterLeyton, Paul Rietzl, Gabriel Nassif, Seth Manfield)

Summarizing the Results

As we can see, for most players, for HoF-caliber pro the matches that ran out of time fall in a 1-2% range, and indeed there are rarely enough 1-0/0-1 wins and losses to give us a statistically significant win rate for matches that time out. Players with reputations for being strong technical players tend to be better than average at bringing matches to completion. True to his reputation as a great technical player, Owen Turtenwald's record in this regard is almost unbelievable in that he's only had a single match run out of time in nearly 2000 matches of premiere play!

Honestly, the results did surprise me when it comes to Seth Manfield, the player who kicked off this whole investigation. I was confident that a player with his reputation of playing at a deliberate pace would run out of time in far more matches, but Manfield's profile is very similar to his peers. His % of matches that ran out of time falls squarely in the 1-2% range, and an insufficient number of 1-0 or 0-1 wins and losses to derive a meaningful win rate from.

Then there's Gabe Nassif, a HoFer whose difficult relationship with the game clock is so widely acknowledged that it's something of a running joke on coverage. Here, I want to defend Nassif a little as yes, the numbers do look bad. Not only does Nassif run out of time at a disproportionate rate, his staggering 15-1 non-draw win rate in those matches is beginning to appear statistically significant in its deviance from his typical non-draw win rate (p=0.01). So it certainly seems that Nassif has an advantage in matches that run out of time. However, I think it's important to remember that the core insight of PVToGFSP is that this does NOT mean Nassif is cheating or even angle shooting, simply that his normal and natural pace of play may be creating a problem. I feel the need to emphasize this point, as I know that nuance can sometimes be lost when a single eye-popping stat is presented.

Gabriel Nassif has such a body of documented work in which he plays extremely slowly - including on MTGO where, unlike tournament Magic, it is never in your interest to take up too much time - that I think it's basically impossible to believe that he is intentionally stalling his opponents. Indeed, one reason I find Nassif's streams and commentary educational to watch is that he is such a deliberate player, and goes to extreme lengths to consider every possible permutation of even the most basic play.

All that said, at least from the numbers there is reason to believe that consistent with PVToGFSP, Nassif's pace of play may be creating an unfair advantage. The solution, as PVDR originally articulated in his podcast, would be for the DCI to harden their rules and enforcement philosophy when it comes to pace of play.

Cavils, Caveats, and Conclusions

I've titled this article a rough statistical analysis for a reason. There are always nuances that our statistics cannot cover, most importantly, as I've mentioned before in our inability to easily determine when a 1-1 draw is a "good" or "bad" outcome for the player.

In addition, slow play or even stalling need not necessarily result in a match that runs out of time; slow play can create advantages even when the match does not run out of time, by putting additional time pressure on the opponent. Indeed, Ondrej Strasky's allegation against Seth Manfield that began this whole conversation was about a match which the players actually completed in time and Manfield won 2-1! Regardless of whether or not we believe Manfield was stalling in that specific case, we must acknowledge that stalling can sometimes still create a complete match result.

The usual reservations about the accuracy of our data set applies - MTGELOproject relies on the official reported tournament results, and sometimes games that end 1-0 might be submitted as a 2-0 result if one player was clearly going to win anyway or because "it doesn't matter," etc,

In addition, while it certainly appears true that Nassif plays more slowly than his elite peers, running out of time at over twice the rate of most HoF-caliber pros, let's place Nassif's 4.3% of matches that ran out of time in a slightly different context: this rate would translate into two matches running out of time for every three 15-round Grand Prixs. This doesn't seem quite so bad, especially compared against the average player. Speaking for myself, I ran out of time in a match in the very first Grand Prix I played in... and I didn't even make day two.

And finally, Gabriel Nassif's impressive win rate in games that run out of time might be somewhat a product of his deck selection - knowing himself to be a player at risk of running out of time, Nassif may be favoring decks with strong Game 1 matchups. In additional, several commenters have pointed out that the control decks Nassif favors tend to "win slowly and lose quickly," which might also account for why his non-draw win rate in matches that ran out of time is so much better than his global non-draw win rate: if the games that he loses conclude on average more quickly than the games that he wins.

All that said, I found the results fascinating with regard to Nassif. As I've said, he's a player I absolutely love to hear commentate his own MTGO games because he does play so thoughtfully and deliberately. (Watching him at a PT feature match table, where all we can do is watch him stare at his cards, is a... less engaging experience.) But at least among the game's elite players, Nassif is generally considered to represent the extreme slowest range on the spectrum of pace of play, and it might be time to consider that his naturally leisurely play speed is so glacial as to be a problem in competitive play.