When some people look at the spoiled cards for Avacyn Restored, they think, “That’s not a miracle, that’s the end of the world!”

Like many people, I’m usually not a big fan of mechanics that fundamentally change the way the game of Magic is played. I’m among the people concerned about the miracle mechanic that is being introduced in Avacyn Restored and how it’s going to affect the way the game is going to be played. This isn’t the first time I’ve felt this way.

Avacyn Restored will be the seventy-second Magic set. Over the course of Magic’s nineteen-year history, there have been over one hundred abilities and mechanics introduced, but only seven of them have been true game changers—mechanics that fundamentally changed how the game was played.

While seven mechanics in seventy-two sets may not seem like many, the alarming part is that the two most recent ones appear in the two most recent sets: transform and miracle. Not only does the frequency of this sort of game changer seem to be increasing, but the level of their impact seems to be increasing at the same time. A mechanic like shadow, which rocked the Magic world with its introduction in Tempest in 1997, seems positively tame in comparison to transform or miracle.

Is this a sign of the Magic apocalypse? Is Wizards’ R&D so low on design space that they have to literally create more by altering the game itself? Perhaps the current regime of design rock stars at Wizards is simply more adventurous than past design crews or maybe more bent on putting their imprint on Magic history. Whatever is going on behind those doors, the full impact will only be felt out here in the field.

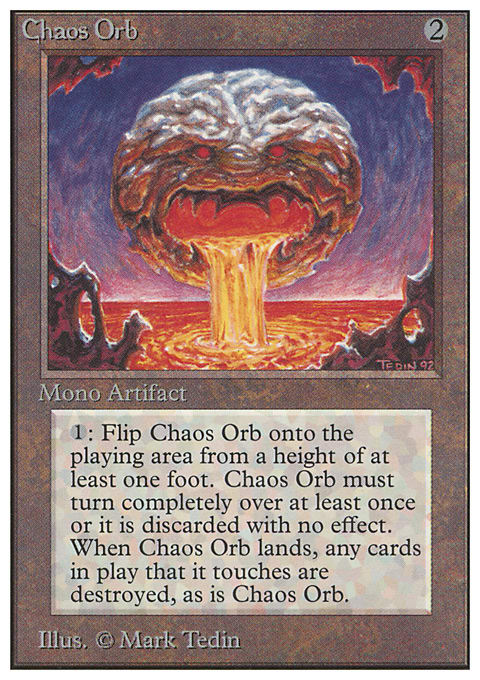

Chaos Orb

The first time I felt this way was very early in my Magic career, only it wasn’t because of a mechanic, but because of a single card: Chaos Orb. If you’ve only been playing Magic for a few years, you probably think the only time the location of your permanents matters is when you need to distinguish between zones of play: your hand, your graveyard, your library, exiled cards, or on the battlefield. Of course, when a card is in play, its location doesn’t matter, right? Unless, perhaps, you want to get in a debate with Paulo Vitor Damo da Rosa about where your lands should be in relation to your other permanents or if you’re playing a feature match at a Pro Tour and you’re busy sending creatures into the “red zone.” If only things were always so simple.

During Chaos Orb’s reign of terror, Magic events felt more like Unhinged or Unglued tournaments than anything resembling “real” Magic. I witnessed Top 8s in which a player’s permanents would take up half of a table that would normally support three matches. Suddenly, this mental sport I loved was being dominated by a card for which not only did dexterity and hand and eye coordination matter, they were crucial. If that wasn’t bad enough, the only way to lessen its impact was to make your board look more like a Frisbee golf course than a game of Magic. For those who are wondering what the heck I’m talking about who haven’t already resorted to a Google search, Chaos Orb was a 2-mana artifact that did this:

Where do I start? (I’ve been waiting almost twenty years to make this rant!) Imagine you’re in a tournament where this card is being used. Are judges carrying rulers to measure the one foot? Are we using instant replay to ensure that it turned over completely? When this card is on the stack, am I allowed to spread my permanents across the length of a football field? You feel my rage . . .

Given that my skills with the Orb were questionable at best and that they cost over $50 (in spite of being restricted), I decided I needed to draw an outraged philosophical line in the sand. Sure, I broke the bank for Moxes and the blue Power cards, but I never ever purchased an Orb. I won several tournaments despite being behind in this particular arms race, but I can only imagine how much better things would have been for me without that card in the format.

Perhaps the worst Chaos Orb story I heard involved my friend Dave Humpherys, perhaps the best Orb master I’ve ever seen. Only Dave knows how many hours of his life he wasted perfecting the use of it, but given his high level of expertise with the card, I imagine it was quite a few. In an event with thousands of dollars at stake, Dave’s biggest loss came in a game in which he had a Chaos Orb in play and a Mana Drain in hand ready to be played. Dave was playing a five-colored deck with no basic lands, so he was a little concerned when his opponent played a Blood Moon. Given that he had an Orb in play, he decided to save his Drain for a more important target. While a great idea in theory, it blew up in his face when he missed with his Orb for the first time in his already somewhat long tournament career. Who knows? Perhaps this experience will influence Dave’s work now that he is one of the leading members of WotC’s R&D team.

When Chaos Orb finally was banned, I was ebullient; now I could focus on playing “real” Magic the way it was meant to be played: without measurements, feats of dexterity, or the placement of my permanents mattering. These things all just felt wrong, as though I could somehow tell they weren’t what the great Richard Garfield had in mind when he first envisioned this wonderful game.

Phasing

After they’ve played for a while, I think most players get a feel for how the game is meant to work and how they think it should work. Since the banishment of the Orb, Wizards has periodically introduced mechanics that initially made players feel that the game was being fundamentally altered and often not for the better.

The first of these was phasing, which was introduced in Mirage block. Cards with phasing left all of the previously known legal zones of play for a turn, only to return “during the untap phase, but before untapping.” Unlike exiled cards, they kept modifiers such as counters and enchantments.

A further source of confusion is that they triggered leaves-play abilities when they phased out, but they didn’t trigger enters-play abilities when they phased in. As you can imagine, this ability caused the most judge calls since banding. While I was delighted every time I cast a Jokulhaups with a Sandbar Crocodile phased out, I’m sure I would have been happier without all of the headaches caused by this ability in tournament play.

The next ability to exploit previously unknown design space was shadow, introduced in Tempest block. While the ability, often referred to as “superflying” at the time, seems tame in comparison to some more recent game-bending abilities, it sent shockwaves through the Magic world at the time. While functionally almost just a parallel ability to flying, there were two major game changes about the ability.

One, you now had a legion of new creatures that, most of the time, could have “can’t block” written on them but that were able to block in situations in which most other creatures couldn’t. Flyers were more interactive than shadow creatures because they could block non-flyers. Initially, many players treated the ability more like flying and kept trying to block non-shadow creatures with shadow creatures. This was a harsh lesson to players who mistakenly thought that shadow was just better than flying.

The other big game change brought about by this ability was the opening of a third major plane of combat. Previously, engagement possibilities were generally binary—either a dude had flying or it didn’t. Now there were 50% more possibilities, which led to much shorter games because of the increase in situations in which creatures couldn’t be blocked and the decrease of creature stalemates. Among other things, you needed to kill fewer of your opponent’s guys to ensure at least one of your guys was going to make it through unblocked.

Morph

During Onslaught block, Wizards stepped even farther out of the box with morph. Now you could play some of your cards face-down and have them perform as a 2/2 for 3 mana without your opponent ever actually seeing the text on the card. This was the first time a card had ever been able to perform a function just because you said so and not because you actually showed your opponent a card saying what it was.

Obviously, you were expected to reveal your morph cards at the end of the game to prove that it actually was a morph, but this sometimes led to awkward post game situations. One of the biggest changes this mechanic brought to the game was a whole additional major category of bluffing intrinsic to the game. Even if you weren’t trying for some kind of mind game, your opponent couldn’t help but wonder: What is it? Should I kill it? Should I block it?

The mana you left untapped had never had such high bluffing potential. Perhaps the worst game change that accompanied morph was the timing associated with unmorphing a face-down morph card—because it was a special action, it didn’t use the stack.

Storm

Onslaught block also introduced us to a particularly nightmarish ability: storm. When you cast a card with storm, you were forced to go back and retroactively track your activity that turn. While it’s a seemingly harmless ability in Limited, it was in a Constructed deck designed to really abuse the ability where the infernal torment of storm was fully realized. It was pretty easy for me to have a double-digit number of spells played in a turn before playing a spell with storm. If I hadn’t telegraphed my play by visibly tracking the spells I’d been casting that turn, how could my opponent and I conclusively agree on the storm count?

In a foreshadowing of the problems that might be on the horizon for miracle, the technically correct play would have been to visibly track your spells cast every turn in every game of Magic you played, even if your deck contained no storm cards. Yikes. The other annoying thing about storm was that it made permission weirdly useless—countering a card with storm failed to counter the storm effect of the card.

Planeswalkers

The game changed again in Lorwyn with the introduction of an entirely new and complex card type: planeswalkers. Unlike the game-changing and game-bending mechanics mentioned above, we’re still stuck with, ahem, lucky enough to still have this one. There are many uniquely annoying qualities to planeswalkers:- 100% of them require tracking.

- 100% of them are text-heavy, with vast quantities of information that both players need to process.

- 100% of them are mythic rares, another historically recent game changer from Wizards with questionable merit.

The big design space they’ve invented/opened up is the concept of having more than one “planeswalker” for your creatures to choose to attack, the one on the battlefield and the player in control of it. Perhaps the most annoying thing about them is that, almost by their very nature, they’re overpowered. Every one of them that has been released so far is easily capable of dominating a Limited game if it hits the board. Most of them have been used to powerful effect in Constructed as well, including Jace, the Mind Sculptor, perhaps the most powerful card printed in the last several years.

Transform

Fortunately, the painful memories of Chaos Orb have helped me keep these mechanics in perspective, and I haven’t been that bothered by any of them until Innistrad and the introduction of transform.

The problem with transform isn’t even the mechanic itself—it’s the impact of a double-sided card on organized play. Ideally in Draft, you closely track the movements of all of them around the table and their final resting places. At the same time, you need to be paying attention to your own Draft and also making sure you don’t give the impression of looking at things you’re not supposed to be looking at at times when you’re not supposed to be looking at them. Judging Drafts and defining and enforcing appropriate behavior was already hard enough without this added headache.

While I dislike feeling forced to play with sleeves, the things that bother me more are the unsightly checklist cards that many players use. Unless I have the entire text of every transform card in my deck memorized, I also find it a little challenging not to telegraph when I’ve drawn one.

Miracle

Apparently unwilling to give me even one set to calm down after having to deal with transform, Wizards is now going to bedazzle us with the miracle mechanic. Cards with this mechanic will have two costs. You can either cast them at discounted costs immediately when you draw them or play them later at a somewhat inflated cost. As a result, these cards will usually be either a little too good or a little bit too bad. Also, perfect play will involve scrutinizing every single card you draw as if it has miracle and you’re considering the possibility of revealing it—even if you’re not playing with any miracle cards.

One of the things these mechanics all have in common is that they become much less annoying when being used online. The problems with transform are removed completely. Weird timing rules are enforced precisely, planeswalkers are always accurately tracked, and so on. Perhaps this is just a coincidence, or perhaps Wizards R&D is increasingly starting to view Magic as a digital product.

While I suppose this could be a sign that R&D is running out of good ideas or design space, I’m not particularly worried. If I can survive and even thrive in a format that included Chaos Orb, I’m ready for the things that the current R&D regime is going to throw at me. I’ve even grown accustomed to transform, so how hard can it be to believe in miracles? It doesn’t mean I have to like every mechanic, of course.